| Brief Article, Biomed Biopharm Res., 2023; 20(2):84-96 doi: 10.19277/bbr.20.2.325; Bilingual PDF [+]; Portuguese html [PT] |

Food insecurity and sociodemographic factors among university students: an exploratory study

Leandro Oliveira 1 ![]() ✉️ , Tiago Figueiredo 2*, Mel Martins 2*, Nicole Owen 2*, Francisco D’Orey 2*, & Carina Rossoni 2,3

✉️ , Tiago Figueiredo 2*, Mel Martins 2*, Nicole Owen 2*, Francisco D’Orey 2*, & Carina Rossoni 2,3 ![]()

1 - CBIOS - Center for Biosciences & Health Technologies, Universidade Lusófona, Av. Campo Grande 376, 1749-024 Lisboa, Portugal

2 - Escola de Ciências e Tecnologias da Saúde da Universidade Lusófona, Av. Campo Grande, 376, 1749-024, Lisboa, Portugal

3 - Universidade de Lisboa – Instituto de Saúde Ambiental da Faculdade de Medicina, Avenida Professor Egas Moniz, 1649-028 Lisbon, Portugal

* These authors made an equal contribution to the development of this study.

Abstract

Food insecurity is a situation that occurs when an individual does not have physical, economic, and social access to healthy food to satisfy their basic nutritional needs. University students can be a vulnerable population group in the face of food insecurity due to limited financial resources, and increased costs associated with studies. This exploratory study aims to assess the prevalence of food insecurity and its relationship with sociodemographic factors in higher education students. To this end, an online questionnaire was developed and disseminated by institutional email and Facebook to the students. The sample had 62 participants, mostly female (85.5%), attending bachelor (88.7%) in a public higher education institution (50.0%). About 27.0% of the students’ households were food insecure. Correlations were found between insecurity and certain variables, namely, it was observed that the greater the food insecurity,, the greater the age and body mass index, and the lower the monthly income of the household. A correlation was also found regarding the student worker status. These results may be taken into account for the development of new studies with university students with a view to exploring factors related to food insecurity.

Keywords: food insecurity, university students, higher education students, food

To Cite: Oliveira, L. et. al (2023) Food insecurity and sociodemographic factors among university students: an exploratory study. Biomedical and Biopharmaceutical Research, 20(2), 1-13.

Author correspondence:

Received: 27/10/2023; Accepted: 15/12/2023

Introduction

Food insecurity is a situation in which an individual does not have physical, social, and economic access to resources and foods that meet their nutritional needs within an active and healthy life. At the household level, food insecurity can range from a food security situation where there is consistent access to healthy food, to a situation of high food insecurity in which there is a reduced food intake among one or more family members. Also, adult food consumption is usually affected before the impairment of child food consumption (1).

Food insecurity is not just a problem for developing countries, it is a global problem that also affects countries considered developed like Portugal (2). Between 2011 and 2013, Portugal registered an increasing tendency in the prevalence of food insecurity, and in that period about 50% of households were in a food insecurity situation. This tendency reversed to 45.8% in 2014 (mild food insecurity: 29.7%; moderate food insecurity: 9.5%; severe food insecurity: 6.6%) (2). However, this study was before the COVID-19 pandemic. A study carried out during the pandemic reported that 1 in 3 Portuguese (3) was at risk of food insecurity, and a recent study with data from the first half of 2021 points to a prevalence of 6.8% in the Portuguese population (4). However, no studies were found focusing on university students in Portugal.

Food insecurity in university students has also been associated with worse eating habits and with a higher risk of obesity (5, 6). Knowing the factors related to food insecurity is important for the development of interventions that mitigate this problem through a holistic and integrated approach, defending food systems that support the acquisition and supply of healthy food, acquired in a fair and dignified way and that satisfy the needs of university students (7). Thus, the objective of this study is to assess the prevalence of food insecurity and its correlation with sociodemographic factors among university students in Portugal.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional and exploratory study aimed at assessing the prevalence of food insecurity in higher education students and relating it to sociodemographic factors. The inclusion criteria consisted of being a Portuguese higher education student and being over 18 years old. We have not established any further exclusion criteria. An online questionnaire, through the Google Forms® platform was used for data collection, and all data were self-reported. The data collection questionnaire comprised four sections: sociodemographic characterization (sex, age, course degree and institution attended, household, smoking and alcohol consumption habits, anthropometric data); adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern; food insecurity; and physical activity. The questionnaire was made available throughout the month of May 2022 and was distributed to students at the School of Sciences and Health Technologies at Universidade Lusófona via internal email. Additionally, it was shared on Facebook® to reach external students, resulting in a convenience sample.

The body mass index was calculated through weight and height and classified according to the criteria of the World Health Organization for adults (8).

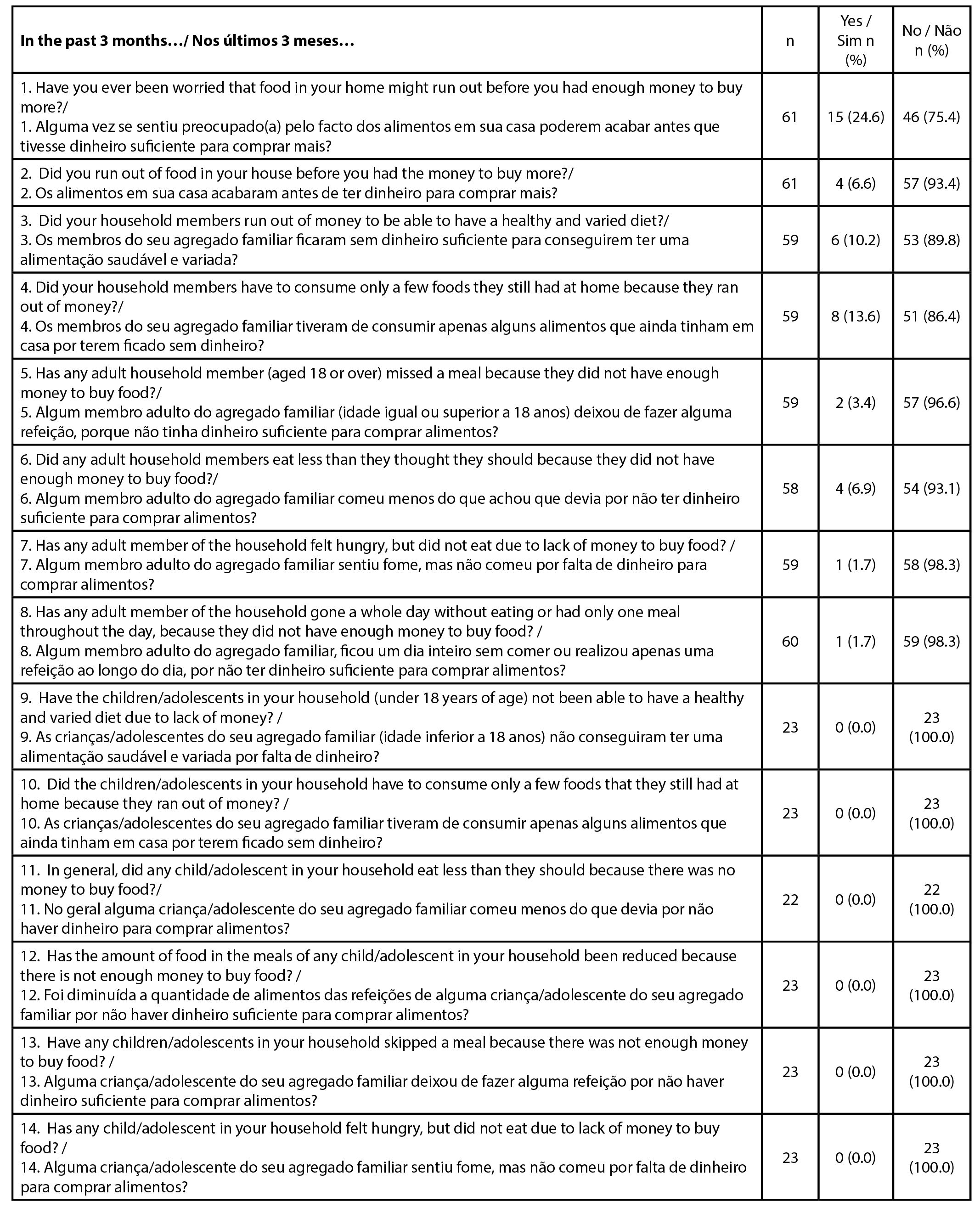

Finally, to assess food insecurity, the Food Insecurity Scale validated for the Portuguese population was used (9). This instrument consists of 14 closed-ended questions with a “yes” (score: 1) or “no” (score: 0) answer referring to the last 3 months. The total scores for households without children determine the categorization of food insecurity levels as follows: food security (0 points), mild food insecurity (1-3 points), moderate food insecurity (4-5 points), and severe food insecurity (6-8 points). Similarly, for households with children, the sum of the scores leads to the classification of food insecurity levels as follows: food security (0 points), mild food insecurity (1-5 points), moderate food insecurity (6-9 points), and severe food insecurity (10-14 points). In this work, only the sections referring to sociodemographic characterization, and food insecurity will be this work.

Ethical considerations

Information was provided to all volunteers about the study and informed consent was provided in which the objective and protocol of the study were explained in detail, confidentiality and exclusive use of the data collected for the present study were guaranteed, and the data were treated to ensure anonymity. Data collection began only after the volunteer agreed to participate in this study (selecting the option: “I have read the information, and I agree to participate in the present study”), otherwise, the questionnaire would end immediately. The study was conducted following the ethical norms established in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical norms and was approved in the scope of the process P01-23 by the Ethics Committee of the School of Health Sciences and Technologies of the Lusófona University.

Statistical analysis

The IBM® SPSS® Statistics software, version 26 for Windows, was used to conduct the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were based on the calculation of means and standard deviations (SD), medians and percentiles (P25; P75) and absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. Fisher’s exact test was applied to assess the independence between pairs of variables, while the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare mean orders between independent samples. Finally, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was applied to assess the degree of association between pairs of continuous variables. When p<0.05, the null hypothesis was rejected.

Results

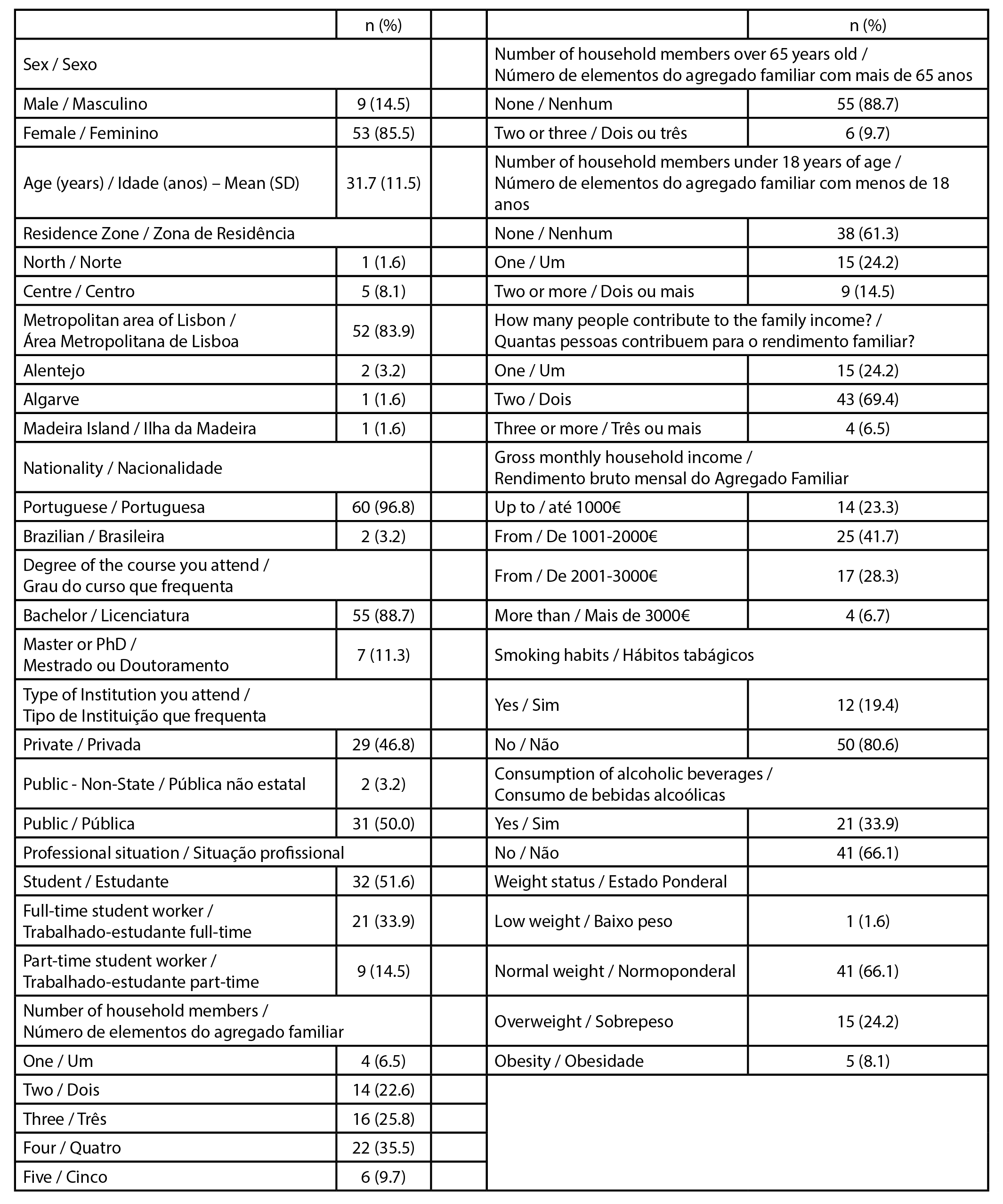

The present study had a total of 62 higher education students. However, due to the lack of answers to some questions, we only obtained 52 complete responses for the food insecurity scale. The socio-demographic characterization and the ponderal state of our sample is presented in Table 1. The majority of the sample consisted of individuals of the female sex (85%), with a mean age of 31.7 years, of Portuguese nationality (96.8%), residing in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon (62.9%), were exclusively students (51.6%), and attending a bachelor (88.7%) in a public higher education institution (50%). Regarding the household, the majority were constituted of three or more elements (71.0%), without children (< 18 years old) (61.3%), elderly (90.2%), without unemployed (75,8%), and two elements contributing to the family income (69.4%), whose household's net monthly income was between 1001€ and 2000€ (41.7%). Most of the students did not smoke (80.6%) or consume alcoholic beverages (66.1%). Regarding their weight status, 66.1% were classified as normal weight.

| Table 1 - Sociodemographic characterization and weight status of the sample. |

|

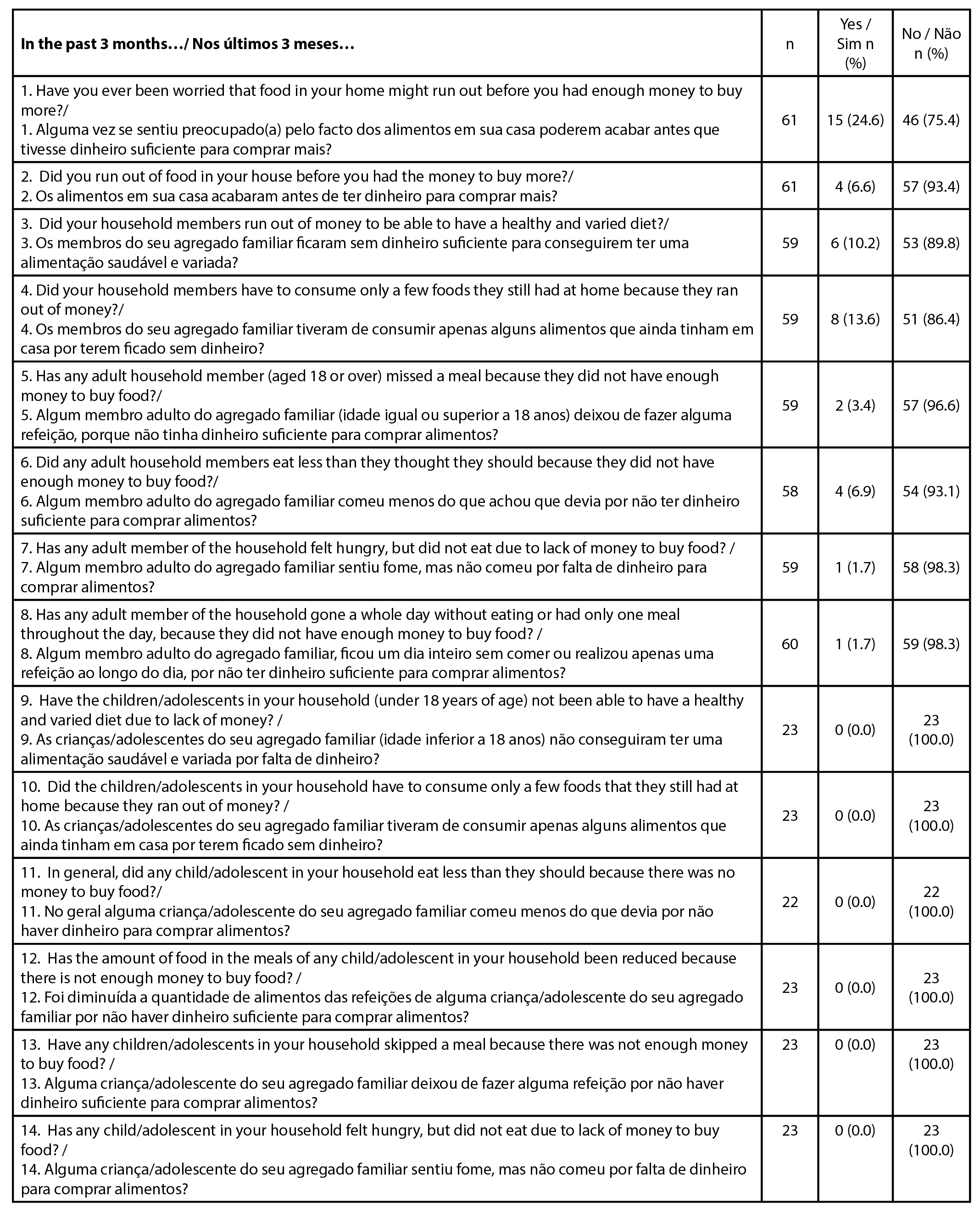

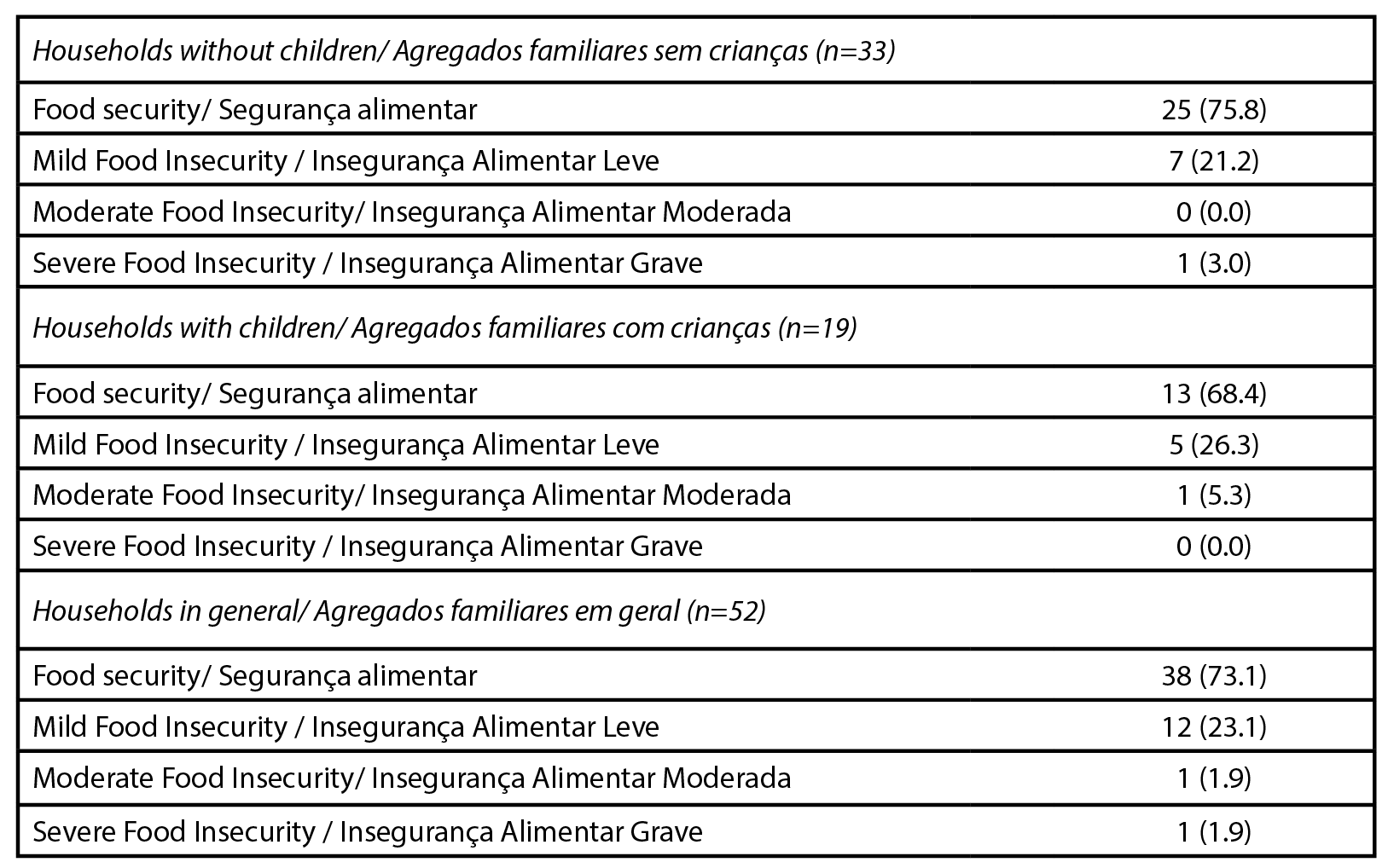

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of the assessment of food insecurity in the students' family households. In general, the reported situations of food insecurity arise from the perception of the possibility of lack of food (23.1%), with situations of effective lack of food being less prevalent. In the households with children, no participant reported situations of food insecurity related to the children (questions 9 to 14 of the food insecurity scale). Households with children presented a higher prevalence of food security when compared to those without children (75.8% vs. 68.4%). Approximately 26% of the students’ households were classified as having some degree of food insecurity (mild, moderate, or severe). Of these, the majority were at a mild degree of food insecurity (23.1%). One of the households (1.9%) was in a situation of severe food insecurity.

| Table 2 - Assessment of food insecurity in student households. |

|

| Table 3 - Classification of the level of food insecurity in student households. |

|

Table 4 shows the relationship between food insecurity and sociodemographic factors. The higher the age and body mass index, the greater the level of food insecurity, and the higher the monthly income of the household, the lower the level of food insecurity. Student-workers had a higher prevalence of food insecurity than students. No relationship was found between food insecurity and gender, the type of institution students attended (public vs. private), being a smoker, or consuming alcoholic beverages. Also, no correlations were found between food insecurity and the number of household members, number of household members over 65 years old, or number of household members under 18 years of age.

| Table 4 - Relationship between food insecurity and sociodemographic factors. |

|

| *p<0.05; **Median (Percentile 25; Percentile 75); # Mann Whitney test; ## Spearman correlation; ### Kruskal-Wallis test |

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of food insecurity and relate it to sociodemographic factors in higher education students in Portugal. University students face several challenges to eating healthily. In some cases, they must learn how to cook and buy food, eat meals away from home with colleagues, balance university and other financial obligations, and adapt to a new food environment away from the household (6). Despite the importance of the study of food insecurity in higher education students, no studies were found in Portugal on food insecurity in this specific group, thus the data of the present study will be compared with those available to the Portuguese population in general and with international studies in university students.

The prevalence of food insecurity in our sample was approximately 27%. If we compare this result with a study conducted on the Portuguese population before the pandemic (2), the value found in our study is lower (26.9% vs. 50.0%). However, compared to a more recent study in a sample of 882 residents in Portugal, our value is higher (26.9% vs. 6.8%) (4). This may be due to the fact that before the pandemic, students had state support (scholarships, accommodation, etc.) that met the needs of students, or there was a certain protection on the part of the household that was organized in order to provide basic conditions to students. After the pandemic, the cost of food, accommodation, and transport, among other expenses, have increased, and support may not have increased proportionally (by the state and/or household) and thus students have been placed in a more vulnerable position, with implications for their diets (7).

At an international level, our results are in line with a study that involved eight universities in the United States and found a prevalence of food insecurity between 19.0% and 34.1%, with an average of 25.4% for the entire the sample (5). However, other studies in the US report a higher prevalence of food insecurity among university students (52.3% (10); 32.0% (6)). All these studies were based on data collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. A more recent study (7) with students from an Australian university reported a prevalence of food insecurity of 41.9%, also higher than that found in our study.

A positive association was found between food insecurity and age, a possible explanation for this could be the fact that our sample has a high percentage of student-workers and is older than would be expected to finish a degree (between 21 and 24 years old), this is in agreement with another study (6) that reports a higher prevalence of food insecurity in student-workers.

The relationships found between food insecurity and body mass index and income are in agreement with the literature (5), once studies have reported a positive relationship between food insecurity and less healthy eating habits which can lead to overweight (5, 10). Furthermore, the negative relationship between food insecurity and household income is also consistent with other studies (6). The price of food can have an important impact on these two variables that influence food choice. Some studies (6, 10) report that healthier foods, with a high nutritional value (for example, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean meats) may have a higher cost compared to foods that are more energetic and have poorer nutritional quality (foods rich in fat and simple sugars and low in dietary fiber).

These results point to the need to develop programs that promote food security aimed at higher education students, however further studies are needed to support these exploratory results on insecurity in higher education students.

Study limitations and future directions

As with any study, this work has some limitations. We can highlight its transversal design that does not allow the extrapolation of the results. In addition, a convenience sample was used, and the sample size is also reduced. Furthermore, the fact that the data are self-reported may lead to the responses being subject to social desirability. However, it is important to highlight as a strong point the fact that we used a scale validated for the Portuguese population and widely used in several studies within this theme.

In future works, a study with a larger and better-distributed sample would be important to draw more solid conclusions about the relationship between food insecurity and associated factors, including adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern. Another interesting aspect would be to relate food insecurity to the factors that influence the choices of food consumed, culinary skills, or health status. The development of assessment tools for the Mediterranean dietary pattern adapted to the Portuguese population is also necessary, as mentioned previously.

Conclusion

In this study, a high prevalence of food security (73.1%), and overweight (32.3%) were found. Correlations were found between insecurity and certain variables, specifically, that the greater the food insecurity, the greater the age and body mass index, and the lower the monthly income of the household. Student workers had a higher prevalence of food insecurity. Although they cannot be extrapolated, these results can be used for the development of future investigations in this area, and this study, consistent with others, has pointed out possible relationships between food insecurity and certain sociodemographic factors.

Authors Contributions Statement

LO, TF, MM, NO and FD, conceptualization and study design; TF, MM, NO and FD, data collecting: LO and TF, data analysis; LO, TF, MM, NO and FD, drafting, editing, and reviewing; LO and TF, tables; LO and CR, supervision and final writing.

Funding

This research was funded by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P. (Portugal), under the DOI 10.54499/UIDB/04567/2020 and DOI 10.54499/UIDP/04567/2020 projects.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to all participants in the study.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare there are no financial and/or personal relationships that could present a potential conflict of interests.

References

1. Kuku, O., Gundersen, C., Garasky, S. (2011). Differences in food insecurity between adults and children in Zimbabwe. Food Policy 36, 311-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.11.029

2. Gregório, M., Graça, P., Santos, A. C., Gomes, S., Portugal, A.C., Nogueira, P.J. (2017). RELATÓRIO INFOFAMÍLIA 2011-2014 – Quatro anos de monitorização da Segurança Alimentar e outras questões de saúde relacionadas com condições socioeconómicas, em agregados familiares portugueses utentes dos cuidados de saúde primários do Serviço Nacional de Saúde. Lisboa: Direção-Geral da Saúde

3. Direção-Greal da Saúde (2020) REACT-COVID - Inquérito sobre alimentação e atividade física em contexto de contenção social.Lisboa: Direção-Geral da Saúde.

4. Aguiar, A., Pinto, M., Duarte, R. (2022). The bad, the ugly and the monster behind the mirror - Food insecurity, mental health and socio-economic determinants. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 154, 110727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110727

5. El Zein, A., Colby, S. E., Zhou, W., Shelnutt, K. P., Greene, G. W., Horacek, T. M., Olfert, M. D., & Mathews, A. E. (2020). Food Insecurity Is Associated with Increased Risk of Obesity in US College Students. Current developments in nutrition, 4(8), nzaa120. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa120

6. Hiller, M. B., Winham, D. M., Knoblauch, S. T., & Shelley, M. C. (2021). Food Security Characteristics Vary for Undergraduate and Graduate Students at a Midwest University. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(11), 5730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115730

7. Kent, K., Visentin, D., Peterson, C., Ayre, I., Elliott, C., Primo, C., & Murray, S. (2022). Severity of Food Insecurity among Australian University Students, Professional and Academic Staff. Nutrients, 14(19), 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193956

8. World Health Organization. (2000). Obesity : preventing and managing the global epidemic : report of a WHO consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization,

9. Gregório, M.J. (2014). Desigualdades sociais no acesso a uma alimentação saudável: um estudo na população portuguesa. [Ph.D. thesis, Faculdade de Ciências da Nutrição e Alimentação da Universidade do Porto]. https://sigarra.up.pt/fcnaup/pt/pub_geral.pub_view?pi_pub_base_id=34228

10. Leung, C. W., Wolfson, J. A., Lahne, J., Barry, M. R., Kasper, N., & Cohen, A. J. (2019). Associations between Food Security Status and Diet-Related Outcomes among Students at a Large, Public Midwestern University. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(10), 1623–1631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.06.251